TL;DR

Intel Hyper-Threading won’t double your cores for free but it does improve your system’s overall throughput to certain extent.

The story begins here…

Recently at work we are building a new system to replace an old relic which includes some heavy batch processing works and I was tasked with rebuilding one such batch in this brand new world. After a while, the work is done and now it is time for us to run some performance testing comparing the freshly built batch against its predecessor.

A little details on our batch

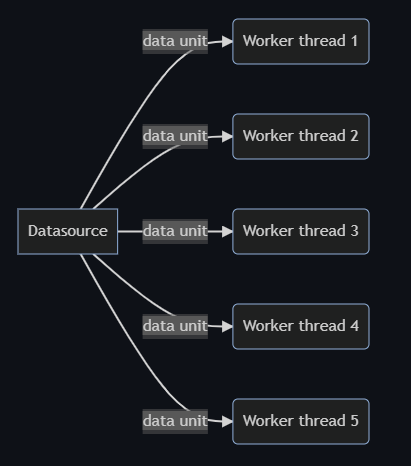

The input data set is divided into thousands of smaller units to leverage the power of distributed computing. This remains unchanged for both the old system and the new one.

Our setup

The old system runs its batches on a proprietary server grid with a fixed amount of on-premise servers but the number of executors(a similar term as Google Cloud Dataflow’s worker harness thread) it is allowed to use is artificially limited.

The new system runs its batches on Google Cloud Dataflow that automatically scales up the worker machine count adapting to the workload.

To match the setup of the old system, we placed a limit on the maximum number of the worker machines which it is allowed to scale up to with –max-workers. i.e. if the old system is limited to use 100 executors and the worker machines Google Cloud Dataflow uses have 4 vCPUs each, we set –max-workers=25 resulting in 100 vCPUs in total. Spoiler alert: this turned out to be not exactly as expected later on.

Furthermore, to ensure consistent performance and match the CPU generation with the on-premise servers where the old system runs it batches, we picked the c2 machine family for Google Cloud Dataflow to use with –worker-machine-type.

Since the underlying libraries responsible for carrying out the core calculation logic remain the same, we were expecting to see similar performance as the original.

Oops!

When the result came in, we were all surprised. The new system’s batch was much slower than the old one. To take a closer look and eliminate noise introduced by IOs and worker autoscaling delays, we decided to profile the time spent on the core calculation logic of individual data units and compare that. Spoiler alert: this later also turned out to be more tricky than thought.

To our surprise(again!), while the old system only spent about 2.8 minutes per data unit, the new system spent roughly 4.9 minutes, almost doubling the time.

How on earth is this happening? The underlying logic are identical!

The moment of eureka

Digging through Google Cloud’s documentations, we realized that the term vCPU does not mean physical CPU cores. What it really means is logical cores provided by Intel Hyper-Threading(a technology that allows 1 physical core to behave like 2 cores, more on that later). So a c2-standard-4 worker with 4 vCPUs actually contains only 2 physical cores and our 25 workers with 4 vCPUs each actually only have 50 physical cores in total.

By default the maximum amount of worker harness threads, each processing a single data unit, Google Cloud Dataflow would launch at individual worker machines is identical to the number of vCPUs according to this documentation(we are running on Batch mode). This basically results in 2 worker harness threads, each running on a logical core, sharing a single physical core.

At the same time, due to configuration, the proprietary server grid only assigns the same number of executors as the physical core count to a single server. This means there is only 1 executor occupying a physical core at a time and 100 executors would mean utilizing 100 physical cores.

In a word, our original assumption of 100 vCPUs and 100 executors being equal was wrong.

What is Intel Hyper-Threading?

Well, you can find Intel’s official explanation here.

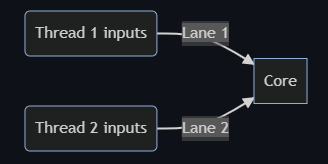

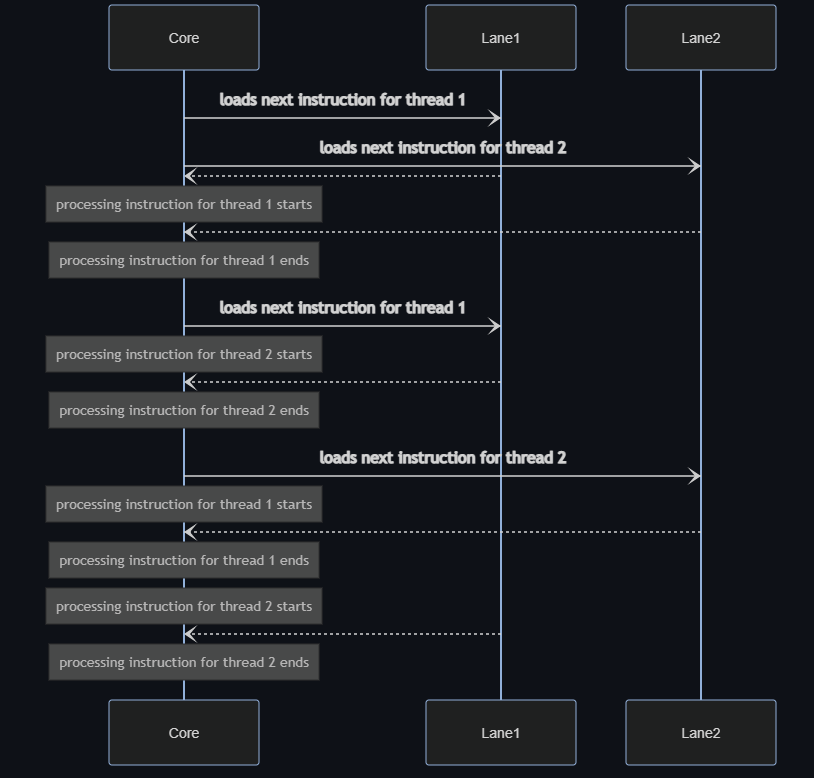

To my understanding, basically it means a core’s processing speed is so fast that there is an ample amount of idle time while it is waiting for instructions to be fetched from memory to registers. To improve efficiency, Intel exposes 2 lanes(called execution contexts) connecting to a single physical core, each transferring instructions of a different thread. Hence, while waiting for the next instruction to be fetched to one of the lanes, the physical core can switch to process the instruction of a different thread available on the other lane instead of idling as depicted below.

Of course, it is still only 1 physical core doing 2 tasks instead of 1 physical core doing 1 single task or 2 physical cores doing 2 tasks and the switch timing can hardly be exactly perfect. Therefore, with Hyper-Threading time spent on individual tasks would be longer but the overall time on both tasks would be shorter, assuming the same amount of physical cores. According to Intel, the overall throughput improvement could be up to 30%.

Below example assumes there are 2 instructions to be processed for each thread.

Sigh, again we were wrong to simply compare the processing time for individual data units since two data units were being processed by a single physical core at the same time in the new system. What actually happening was: the old system took 2.8 minutes to process 1 data unit per core at a time while the new system took 4.9 minutes to process 2 data units per core at a time. Hyper-Threading did provide an overall improvement of 12.5% on throughput but it is obviously unable to counter the 50% reduction on cores. We were simply expecting new system to take the same amount of time while giving it only half the amount of physical cores!

Main takeaways

- Google Cloud’s term vCPUs refers to logical cores instead of physical cores.

- With Intel Hyper-Threading, 1 physical core becomes 2 logical cores.

- Performance on a logical core is not directly comparable with a physical core.

- Hyper-Threading would not really double the amount of cores like magic but it does improve overall system throughput to some extent.