Introduction

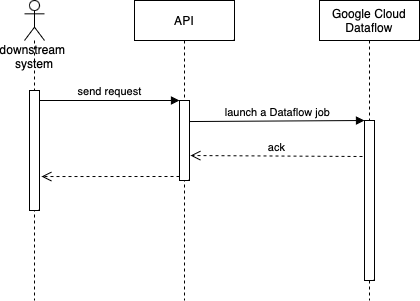

Recently at work, we were asked to implement an API allowing our downstream system to trigger some data processing job on demand.

This data processing job requires certain input from the downstream system so it’s not possible to implement it as a batch job that runs periodically on a schedule.

As the job requires significant computational resources to process, it’s run on Google Cloud Dataflow to leverage distributed computing for scalability. Our initial implementation is rather naive. It launches a new Dataflow job whenever a request is received from the downstream system.

This works perfectly fine as long as jobs are launched relatively infrequently except that this is not the case for us.

The challenge

We soon find out our dear downstream system intends to spam requests almost like a DDOS attack. According to their own estimate, they will send hundreds of requests to our API in the span of a few minutes.

With our initial implementation, this will result in hundreds of Dataflow jobs being launched in a short period of time.

When a job is launched in Google Cloud Dataflow, it needs to startup the worker pool before any processing can take place. This worker pool then again needs to be shutdown after the processing is done. As a result, there is some overhead cost for each job launched, a little bit over 3 minutes to be exact. This is nothing if the workload is heavy and the frequency of job launch is low which is what Dataflow is designed to handle.

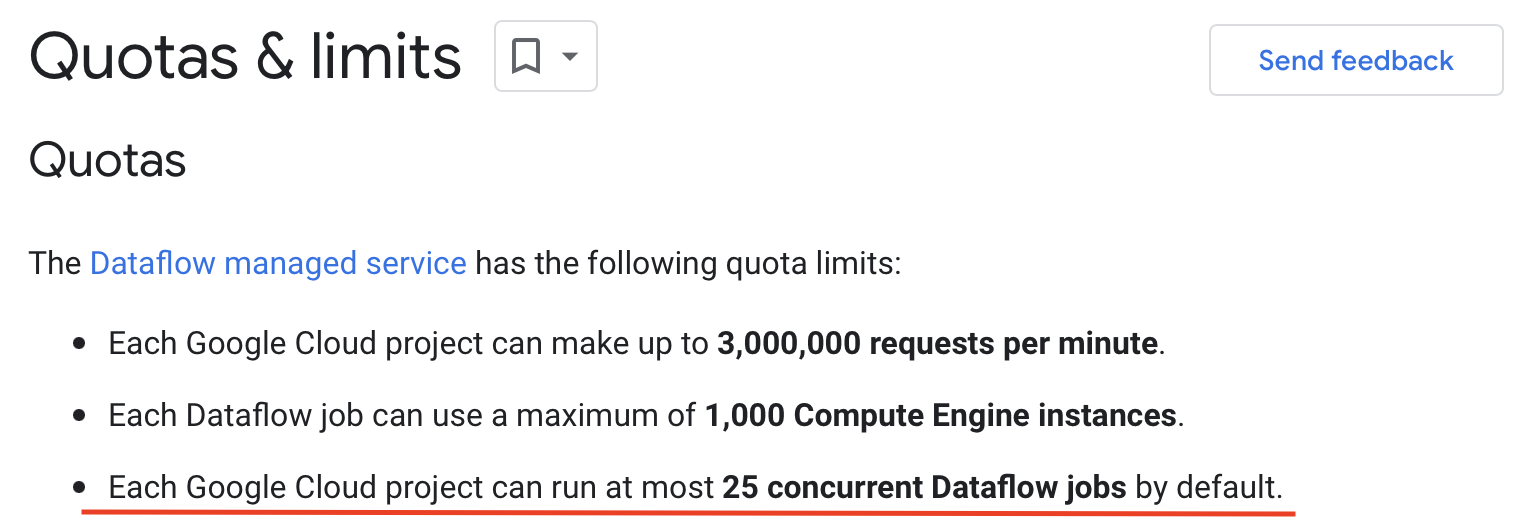

Heck, Google even places a hard limit(25 by default) on how many concurrent jobs there can be for a given project to make this extra clear! Additional jobs would become pending until earlier jobs finish running.

With the pattern in our case, the overhead adds up costing us both in terms of money and time. Google’s limit on concurrent jobs also makes request processing appear to be taking longer than it actually is as some requests need to wait for others to finish before their processing can start.

Analysis time

Upon a closer inspection we found that although a single request on its own might be large(by large I mean it contains a lot of data to be processed which takes more than 30 minutes), most of the requests are rather small.

On top of that, the majority of them usually contain a high percentage of data that has already been processed by other requests. In other words, there is a huge amount of overlapping between the data from different requests. Reprocessing the same data would only yield identical result so it’s really a waste of resources and time.

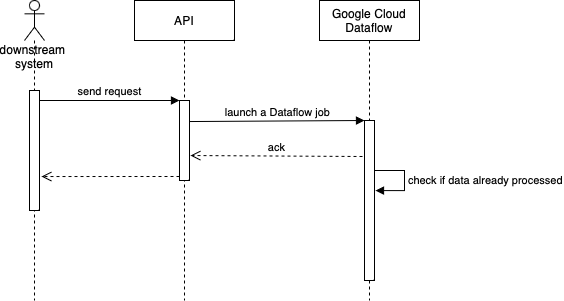

Although we implemented logic to check whether specific data is already processed in DB to avoid processing the same data twice, the problem of overhead and request pending is still not eliminated.

From our observation, most of these small/overlapping requests only take less than 5 minutes in total for the job to finish assuming no pending. Since the startup and shutdown of the worker pool is already taking more than 3 minutes, we are spending more time on the overhead rather than the actual processing which is not justifiable.

The worst case scenario, the worker pool starts up only to find that all the input data has already been processed so it shuts down immediately.

The solution

To cut down the cost of overhead, it’s obvious that the point is to avoid launching excessive Dataflow jobs and lower the job frequency. I.e. we need to downsample the requests.

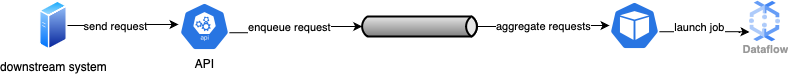

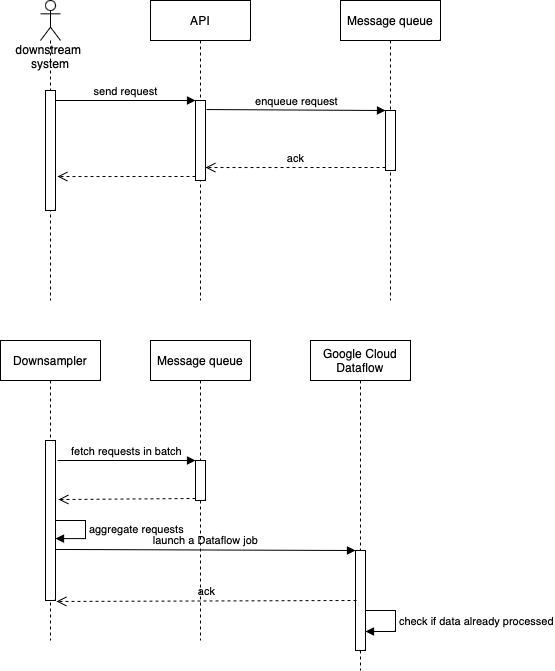

The solution is rather straightforward. Instead of launching a Dataflow job immediately for each request received, we push the request into a message queue. Then we introduced another component to fetch and aggregate the requests from the message queue every 5 minutes by merging the input data sets into a single data set. Finally the downsampling component launches a single Dataflow job for the merged data set.

This basically reduces the overhead costs for tens of hundreds of Dataflow jobs to just one. Since there is only one job launched, the pending time due to Google’s concurrent job limit is eliminated. It also comes with a nice side effect that improves the throughput of the API as it no longer needs to wait for Dataflow to validate and acknowledge the job but simply pushes the request into the message queue.

From the perspective of the downstream system, our API will appear to be more responsive and the processing will give the impression of being faster.

Measuring its effectiveness

With this solution deployed, we proceed to measure how effective it actually is.

From the metrics we gathered in our testing, its effectiveness varies from time to time as sometimes there are only a handful of requests within the 5 minutes span while sometimes there are a lot more.

In one of our observations, 71 small requests are aggregated into a single Dataflow job, saving about 210 minutes of overhead(assuming 3 minutes each job) that would have been spent on worker pool startup and shutdown. The time saving would be even more significant if we also count the pending time.

Conclusion

We are expecting this solution to be more effective in production. During our testing the requests were sent manually with an inconsistent frequency while in production they will be sent automatically as our downstream system runs its batch resulting in a much higher request frequency.

At this point, we are quite happy with what we have achived and it was a fun journey to explore.